Put down your tar and pitchforks. The activities connotated with “cyber security” are vital to avoid the worst consequences of malicious acts that could target computer-based systems. After all, we live in an era where computers are the predominant means we consume information, forming the basis of our knowledge and subsequent actions.

I have been fortunate to work on nationally significant critical infrastructure where we developed function-centric approaches to computer security. Leveraging that experience, I have spent much of my career either working in support of or directly for an international organisation on the proposal, establishment, drafting, consensus building, and maintenance of internationally recognised consensus guidance documents on “information and computer security”.

But why do we use the terms “information and computer” security rather than “cyber security”? While, as with all things that make international consensus, there are a number of elements at play, I remain a strong proponent in favour of this decision within my individual capacity because I have come to believe that the term “cyber security” is harmful, and at least the recognition of that is needed to move forward into a more mature engineering-inclusive approach to security. Let me explain why.

The Ambiguity of “Cyber”

Computer security is only the desktops, but “Cyber” includes the Cloud, right?

A Diplomat, 2022

Computer security doesn’t include the cloud… but the cloud is made of computers?

“Cyber” is an abstract concept inconsistently encompassing various digital, virtual, computer-based, or internet-related ideas. When discussing “cyber security,” interpretations can differ significantly among individuals from diverse backgrounds, such as policymakers, regulators, company directors, engineers, security professionals, and average users. This inconsistency poses a challenge when asserting that “cyber security is everyone’s responsibility.”

The ambiguity surrounding “cyber” can result in confusion or misunderstandings about the scope and focus of “cyber security.” Consequently, it may be difficult to establish clear security objectives, making the definition of strategy, policy, programme and assurance mechanisms inconsistent and resulting in potential gaps in implementation that attackers could exploit. Securing an abstract concept with no universally agreed-upon definition is challenging. Establishing specific security objectives and successfully adopting a graded approach requires a more precise focus.

“Computer security” offers a more appropriate emphasis on protecting computer-based systems regardless of any biases towards their form or function. In all “cyber”-relevant technologies, the common element is using computer-based systems, including workstations, servers, networking devices, IoT, cloud computing, information technology, and operational technology. How these systems perform functions is what matters.

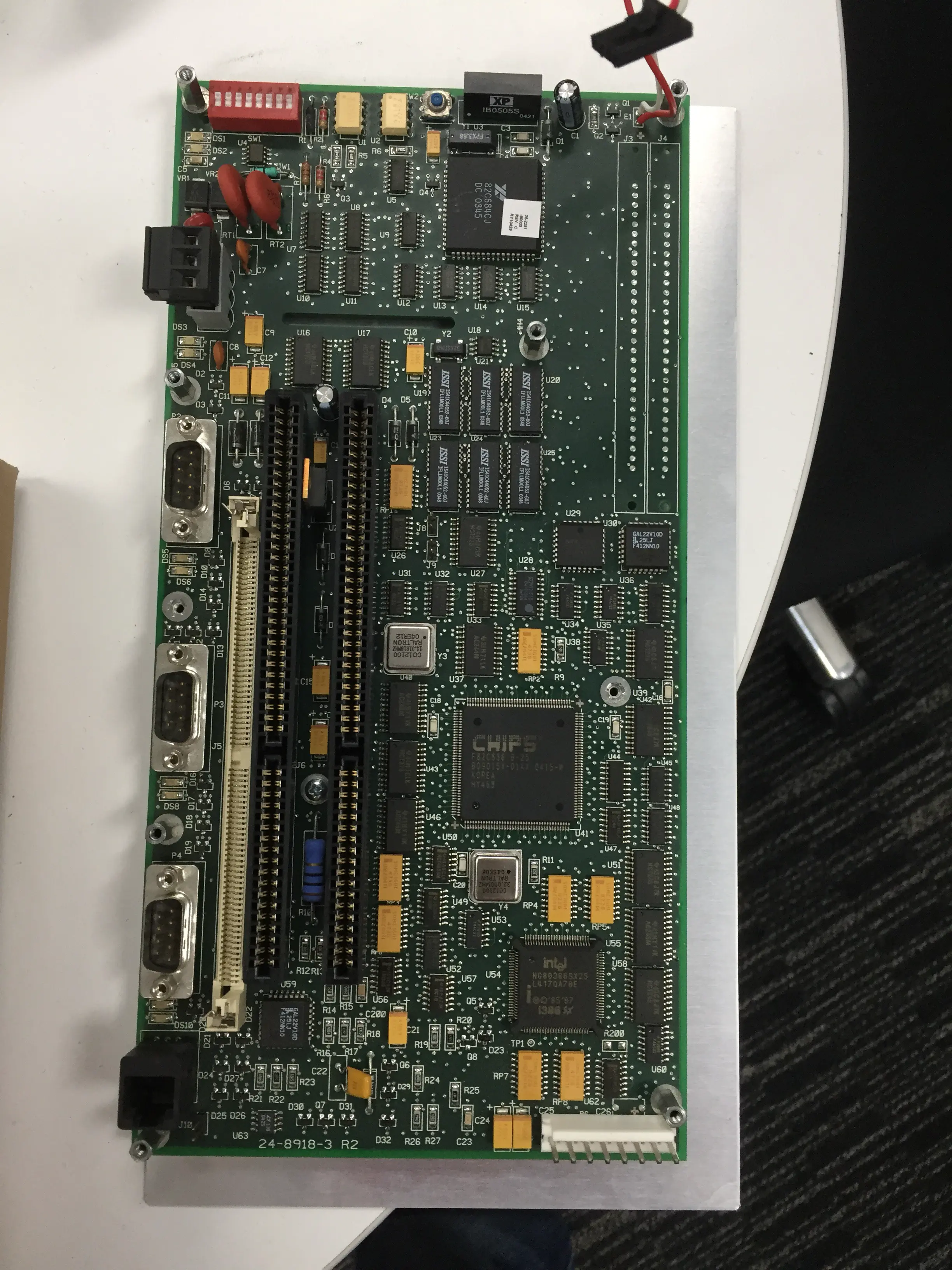

Inside the chassis of a Foxboro CP60 module. Definitely a computer.

Inside the chassis of a Foxboro CP60 module. Definitely a computer.

A computer-based system contributes to the performance of a function, this contribution is understandable, and a security programme can be oriented to preserve the contribution towards the performance of the function. This approach actively encompasses any digital device with reprogrammable logic, such as CPUs and Programmable Logic Devices, as the scope of a computer is well-defined at a technical level. It also takes into account the potential consequences of compromise.

Engineers know when they use computers. With this perspective, it becomes evident that everyone involved in the system lifecycle has a role in maintaining security rather than assigning the responsibility solely to a “cyber” expert. Adopting a tangible, measurable approach to security with a more understood scope can help reduce ambiguity and foster a better mutual understanding of the responsibilities of securing digital systems.

Overemphasis on Specific Technology

We have some clients installing two data diodes operating in opposite directions. The protocol break protects against cyber-attacks.

Security Vendor, ~2017

The prevailing focus of “cyber security” governance leans heavily towards securing information-processing systems. This approach influences workforce training, market solutions, and risk assessment. While some practitioners may perceive a broader meaning behind “cyber security,” the widely accepted understanding remains on information protection. This narrow focus leads to a skewed governance model prioritising safeguarding information and normalising detection, delay, and response strategies aimed at information systems rather than preserving the business functions no matter what systems contribute to their performance.

“Cyber security” overemphasises information security and its technological aspects, often overlooking organisational factors contributing to attaining security objectives such as functions, system design, and existing defence-in-depth and other resiliency measures. This results in a less efficient allocation of security resources. Even when venturing into areas like OT security, the fixation on information-processing technology can overshadow the importance of human factors. Both computers and humans can act on malicious information. Still, the cyber-physical actions of computers often receive more attention than the potential for maliciously misleading human operators into causing unintended consequences (phishing attacks to obtain information are the exception). Without investigation, such incidents may be considered accidents, with the operating organisations and vendors likely having no incentive, or even data, for further investigation when it is attributable to user error.

In my experience, I have seen examples of national critical infrastructure regulations that criminalise attacks on information confidentiality while leaving gaps in addressing breaches of integrity and availability, which may be more consequential in malicious acts. Technical resources are often dedicated to protecting against or gaining visibility into internet protocol-based attacks rather than detecting subversion within engineering networks or business functions.

This approach leads organisations to invest heavily in standalone “cyber security” measures while neglecting the integration of security principles into engineering processes. Consequently, this may result in suboptimal solutions that fail to address the root causes of vulnerabilities and risks. We must ask ourselves: are we striving to maintain the proper performance of business functions, or are we mistakenly believing our responsibility ends with protecting computer systems?

Clarity of Roles and Responsibilities

We don’t have to worry about “Cyber Security”. We are not connected to the Internet.

Reactor Manager, 2018

A respected industry leader once told me that “cyber security is a solved problem. You can only be attacked through physical access, wired networks, wireless networks, supply chain, portable media and mobile devices. Once you protect against those, you are secure.” But who is doing the work? The engineers or the cyber security professionals? At what point in the engineering lifecycle does it occur? More often than not, “cyber security” is considered after design and development with minimal emphasis on security by design. Is this viewpoint just more of a reactive approach?

The normalised approach to security and safety certifications has been to front-load costs during the initial design and development, with few economic incentives for ongoing support and maintenance. While this has shifted over time, there is still an issue due to ambiguities around “cyber security” the full scope of a function-centric systems engineering approach to protecting computer-based systems is not considered part of, or a requirement within, the engineering design process. Information security is the exception, with resources frequently allocated towards protecting sensitive information. All other aspects are relegated to implementing programmes and measures to build a barrier around what are likely fundamentally insecure systems.

Over consecutive years I witnessed two sales pitches for modernising an extensive distributed control system from the same vendor: the first presented an architecture without security considered. The second, the “high security” variant, provided the same architectural diagram, with the same hardware and software, but with logos of cyber security companies such as “Splunk, Cisco, Juniper, and McAfee” scattered around the periphery of the diagram. It was clear at that point that they didn’t see their product as part of a target set, consigning their concerns to the information technology surrounding it. Maybe things have changed now? But where does the boundary exist between the product’s security, the software and hardware enabling the function, and the surrounding environment? Who should be responsible? Do we rely on the insertion of insecure trust into our secure boundary? It’s not like that hasn’t been exploited before.

What would it be like if we had these clear responsibilities established? We could achieve this by securing “computers” and their functions, which would be considered another aspect of good engineering consistent with engineering ethics. Such an approach would have further benefits as many incidents related to computer systems arise from poor engineering practices. A more robust approach to achieving safety and security assurance by design, where there are more specific responsibilities around the engineering of computer systems, could increase general system resilience and robustness, preventing many safety incidents from occurring altogether.

Simplification of Complex Issues

Can’t you just install Anti-virus on the Workstation and call it a day?

I&C Engineer, ~2017

“Cyber security” simplifies complex and multifaceted issues that cross disciplines, through ambiguity reducing them to a binary concept of secure versus insecure and further positioning the entire profession to be seen through a lens of commodity measures and professional services. I had this experience, attempting to justify the security of a complex operational technology system within a nuclear reactor against a set of government controls primarily intended for application to information processing computers.

The systems we were looking at securing performed functions and had an existing engineered approach to assuring safety and security defence-in-depth. Multiple systems would perform the same function and thus deserve protection from external threats and measures for delay, detection, and response that orient towards reinforcing their reliability and independence. The mandated oversimplification of security hinders nuanced discussions and the development of comprehensive strategies for preserving the performance of these functions. Instead, we were, at best, incentivised to build a common boundary around all such devices and declare them secure.

These are all threat-centric approaches. Without more function-centric approaches, encouraging collaboration and cross-involvement between engineering and computer security to address the preservation of the overall engineered function, we will be stuck securing a set of potentially inconsequential computers in manners that may even degrade security.

Fear-driven Market Economics

Did you read the article in Wired today? You should be more worried. If we are hacked, I’ll cut you loose before they take my head.

IT Manager, ~2017

Increasing media coverage and public awareness of cyber threats have intensified concerns about the potential consequences of attacks. High-profile incidents, often involving sophisticated and well-resourced threat actors, have spurred organisations to invest in security measures without fully understanding the specific risks they face. This fear-driven demand has led to a proliferation of “cyber” products and services, with vendors capitalising on the anxiety surrounding cyber threats to promote their solutions as essential and establish long-term vendor lock-in.

In this climate, organisations are influenced by the overdramatisation of “cyber” to allocate resources based on fear and ambiguities surrounding the term rather than through rational risk assessment and the potential for actual risk reduction. The fear of becoming a victim of a cyber-attack, combined with the limited cross-disciplinary knowledge of many “cyber security” professionals, can result in a reactive deployment of the latest security technologies or services without considering their effectiveness in addressing the organisation’s unique vulnerabilities and threat landscape. Such reactivity can lead to suboptimal resource allocation, fostering a market that thrives on fear instead of developing and implementing effective, tailored strategies for meaningful risk reduction.

Stifling Innovation in Engineering

If you don’t call it “cyber security”, I’m not funding it. I don’t care about good engineering. That’s their problem.

IT Manager, ~2016

The trinity of “Cyber security/cyberthreat/cyber-attack” has positioned “cyber” as a threat-focused discipline distinct from engineering, promoting a reactive mindset where security measures are implemented as an afterthought or in response to specific threats. We prioritise resources to detect malicious activity on computer networks with little thought to addressing defensive strategies within the fundamental engineering designs and resulting response procedures. What happens when a threat is detected? Who responds, the engineering team or the computer security incident response team? Who has authority over the equipment?

If a process-aware anomaly detection system has a high-severity trigger, who will be liable when making the call to bring the process to a safe state? These procedures and interfaces likely do not exist or have yet to be considered. Treating “cyber security” as different to the engineering disciplines that develop computer-based systems and the operations teams that use them contributes to a lack of interdisciplinary expertise, where professionals narrowly focus on their respective domains. You will see security functions without communication channels and operations with poor visibility due to a reliance on compromisable digital indicators.

A cyber-attack is not a special snowflake. Conversations need to occur to establish the mechanisms of delay, detection, and response addressed within the engineering design and shared between operations, engineering, and security. There is a misguided view that cyber security incident responders will have complete authority, but that seldom happens.

For the best outcome, we must recognise that many approaches to “cyber security” are just band-aids incentivising the industry to stand in the way of progress. There is a need for real innovation in how we engineer and operate computer-based systems. We can only achieve more effective assurance by recognising that “cyber security” protection is not absolute. Instead, our best approximation will be embedding computer security into the engineering design and building on that to leverage multi-disciplinary approaches to detection, delay, and response.

Conclusion

There are misaligned incentives between engineering and “cyber security”, which I largely attribute to ambiguity in the term “cyber”. Engineering assurance prioritises functionality and cost from the comfort area of existing assessment methodologies, leaving “cyber security” as an exercise for operating organisations. Meanwhile, “cyber security” focuses on defending against cyber threats rather than working to support the assurance of functions those same threats would seek to target.

This misalignment can create tensions and hinder the development of balanced solutions, considering relevant information from both disciplines and meeting engineering needs and security objectives.

Worse still, the symbiotic relationship between first-to-market engineering pressures and the false application of “cyber security”, if oriented to protecting computers rather than preserving functions, will be hugely detrimental to infrastructure security worldwide.

The focus on the robustness and resilience of the performance of functions, understood by both fields and made more tangible with “computer security” rather than “cyber security”, would encourage the adoption of a more holistic systems engineering effort that will go a long way to achieving security by design.

Whichever word, we must recognise that “cyber security” is good engineering. It is not different; it is not unique; it is an assurance function that needs to be considered in the engineering design process, just like safety. After all, when faced with the existence of malicious acts, safety cannot be guaranteed without security.